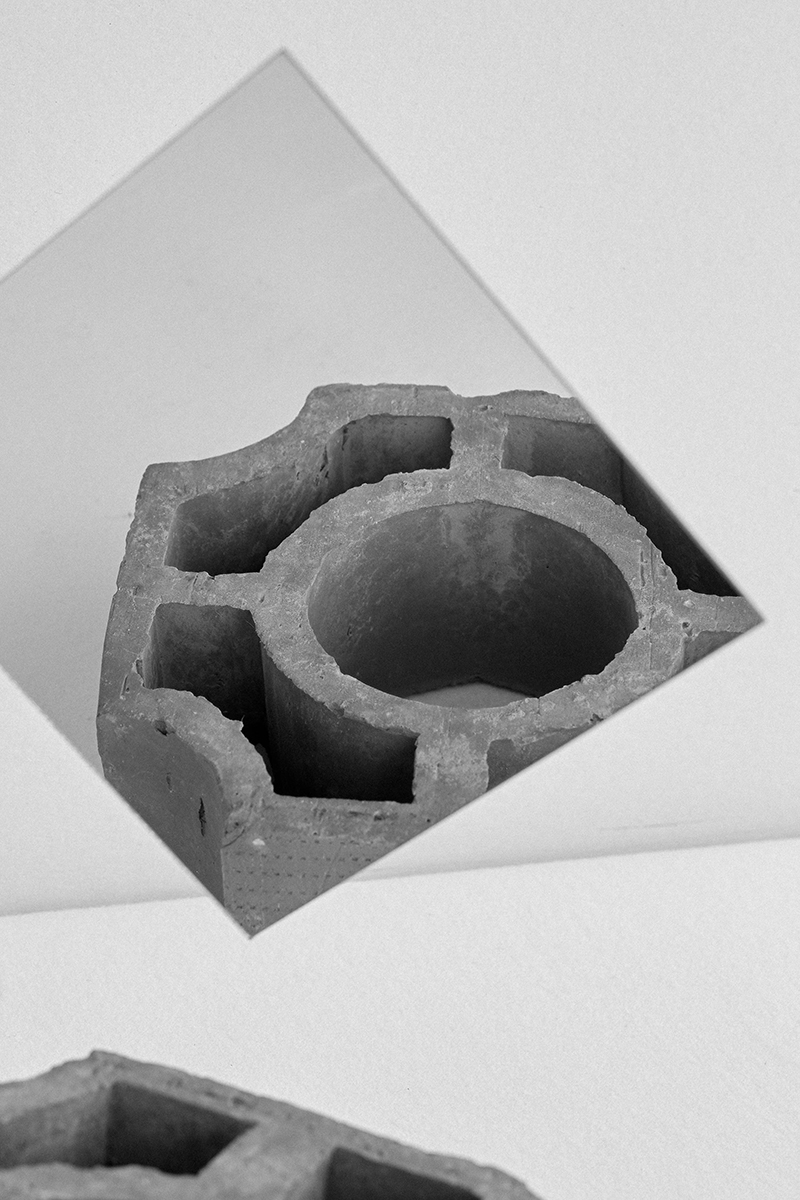

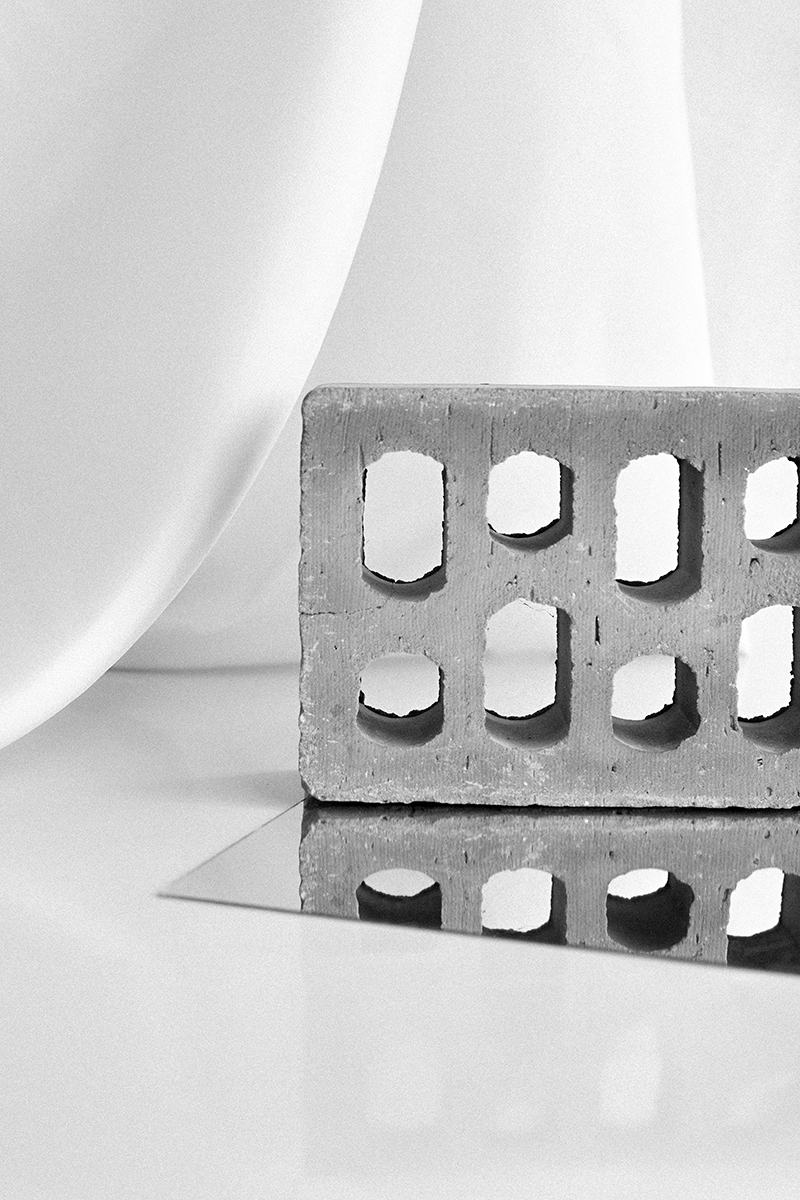

Claustra-Phobia. Mashrabiyas des briques.

In a small village about a hundred kilometres from Tunis, on a section of the motorway, the country roads are lined with cactus and olive trees typical of this remote part of Cap Bon. This was the route that led us to one of the last tile factories near the capital city, where we intended to find terracotta bricks and roof tiles. There is not much left. Items are stacked here and there throughout the factory. Production will soon stop. According to the factory owner, sales have been declining for years. However, for us young architects working at the SEPTEMBRE agency, this is hard to believe. We have spent part of our lives in Tunisia, where, between the 1940s and the early 1990s, ceramics used to be a key material in all local architecture.

Facing the challenge of reconstruction in the post-World war era, a brand-new movement was born: called Mediterranean or Provençal, a local hybrid between the emerging modern movement and a streamlined regionalism.

Indeed, terracotta (a natural material that reveals its true beauty in the sun) was for ages the material of choice for buildings on both sides of the Mediterranean, be it in the form of tiles, bricks, or in the form of a tiled screen called claustra.

Produced on a large scale, this Mediterranean architecture had its own codes and mentors. The major figures were, for the most part, French: Jacques Marmey was the most famous of all, along with Jean Lecouteur, Bernard Zehrfuss, and Jason Kyriacopoulos. However, these names remain unknown to the general public, having been eclipsed by the refined flamboyance of their more modern contemporaries like Le Corbusier, Perret, Loos, and Mies Van Der Rohe. …

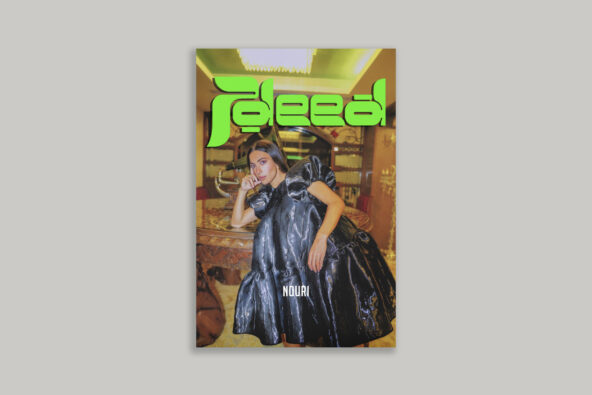

Find the whole article inside Vol.3 of This Orient “The Greater Middle East”. Find the issue here in our store.